Media Unlimited director Magda Abu-Fadil trained Lebanese journalists and media professors on how to detect false information using case studies and various tools in combating the infodemic.

Fact-checking workshop for Lebanese journalists and academics

She introduced the trainees to visual illusions and misleading pictures employed to trick viewers and brought up disinformation about Covid-19 vaccines that spread virally on social media to dissuade people from being vaccinated.

She conducted the three-day workshop, organized by UNESCO and the Lebanese Ministry of Information, in March 2021, and hosted expert Nayla Salibi from Monte Carlo Doualiya Radio to launch the coaching with a review of cyber security and how information disruption can cause great harm when people fall prey to manipulated data.

Monte Carlo Doualiya’s Nayla Salibi explains online risks

Abu-Fadil’s training was based primarily on the UNESCO handbook/course she co-authored “Journalism, Fake News and Disinformation.”

The sessions included participants from Lebanon’s Ministry of Information and National News Agency, Saudi 24 TV channel, Kuwait TV, Lebanon’s OTV, Radio Liban, Télé Liban, LBC TV, Al Arabi Al Jadeed, Univérsité Saint Joseph and Univérsité Saint Esprit Kaslik, among others.

The participants were shown a doctored video that former U.S. President Donald Trump had re-tweeted to attack CNN by falsely claiming it was “fake news” and why critical thinking was an essential tool in combatting disinformation.

Donald Trump retweeted a doctored video to attack CNN

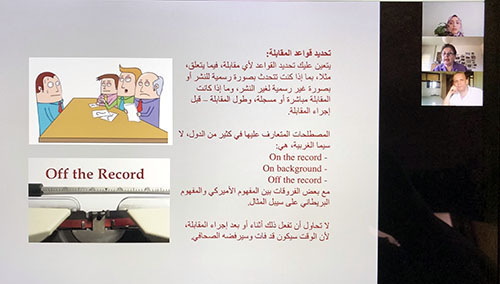

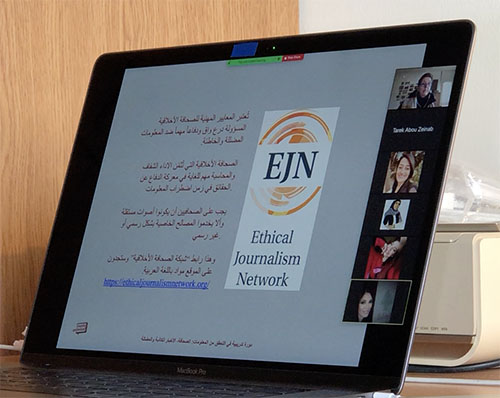

She pointed to the need for media ethics and directed them to the Ethical Journalism Network’s website that provides valuable resources in multiple languages, including Arabic.

The Ethical Journalism network is an integral part of fact-checking

Abu-Fadil broke down the various types of egregious behavior leading to mis-, dis- and mal-information and provided tips on how to avoid them while showing examples with videos that drove home the point.

She also directed their attention to less prominent cases such as satire and parody that can be mistaken for real news and lead to damaging consequences.

The participants viewed a video of on a program to detect distortions in digital photographs that was adopted by Agence France-Presse as well as a video of AFP’s active fact-checking program.

AFP’s Fact Check program

Abu-Fadil presented a case study of pre-digital information verification from her experience as a foreign correspondent and editor with AFP and how the principles of ensuring that information is correct had not changed but that technological tools had made it both a blessing and a curse in trying to avert information disruption.

She provided tips on how to verify user-generated content and what types of questions to ask to ascertain its veracity with several case studies to emphasize the point.

Abu-Fadil further explored the historical background of propaganda and showed a video on the meaning of this news genre.

Adolf Hitler was a master propagandist

The participants were briefed on Media and Information Literacy with all its sub-divisions and how journalists should become familiar with it to better understand the implications of what they produce and disseminate.

Abu-Fadil introduced them to the UNESCO and UN Alliance of Civilizations book “Opportunities for Media and Information Literacy in the Middle East and North Africa,” of which she was the key editor and key author.

The need for media and information literacy

She told them she was the first person to introduce the concept in Lebanon in 1998-99 through a distance-learning project with the University of Missouri School of Journalism when she headed the journalism program at the Lebanese American University.

She also discussed a paper she presented in 2007 at the UN Literacy Decade conference in Doha, Qatar commissioned by UNESCO and entitled “Media Literacy: A Tool to Combat Stereotypes and Promote Intercultural Understanding.”

TinEye reverse image search tool

Abu-Fadil presented a list of tools to detect wrong information on social media platforms, reverse imaging techniques, geolocation, weather assessment and the safe use of chat apps.

Tom Cruise deep fake video

She concluded with examples of “deep fake” videos featuring U.S. actor Tom Cruise and the need to combat online harassment, particularly of women.